Here’s the question that drove us forward:

Is artisan dried pasta worth more money than the cheap boxed stuff? What’s the difference?

To find out, we tasted hundreds of brands, consulted with food scientists and wheat breeders, read research papers, and visited pasta factories. But tonight, we were just going out to eat. We went for an ethereal kind of meal at Torre Del Saracino in Vico Equense. First came an amuse of red bell pepper sorbet with anchovy and green olive. A great palate pick-me-up. Later, a fish course of local merluzzo that was smoked and served on cauliflower crema with a gelee of oyster and tomato water. The plates were expertly conceived and crafted. The flavors clean. Spaghetti al pomodoro was the crescendo of the meal. It was all about one flavor: Mt. Vesuvius tomato. These volcanic tomatoes carry a DOP designation for good reason. Around here, the altitude, sun exposure and unique soil give the pomodori incredible sulphuric umami and a vivid red color like candy apples.

“What brand of spaghetti is this?” we asked a server. He returned from the kitchen and replied, “DeCecco.” Eyebrows rose.

We were a bit surprised. DeCecco makes good pasta, but we expected a local, artisan brand. After all, this region is world renowned for its dried pasta craftsmanship. Nearby Gragnano is even dubbed “The Pasta Capital of Europe.”

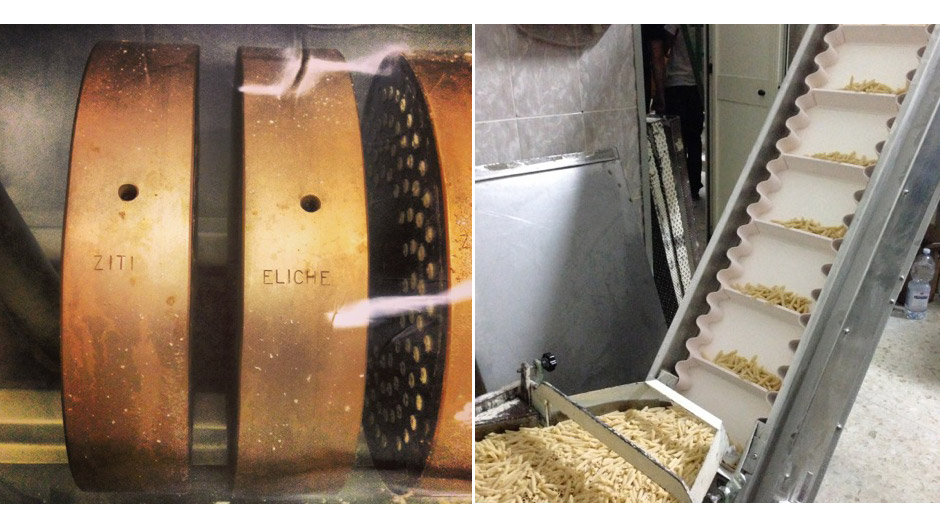

The next morning, we drove to Gragnano and shot some espressos before heading into Afeltra Pastaficio, one of the world’s premier artisan pasta makers. Paolo Torrero showed us Afeltra’s entire operation with pride. From the different flours they use to the variable water-to-pasta ratio to the drying times, Paolo explained how each pasta is crafted with care. Gleaming steel machines mixed the semolina and water, extruded the dough through bronze dies onto white conveyor belts and carried the pasta to wood-frame racks. Then the real magic happened: the drying. Several factors influence the taste and texture of dried pasta — from the flour and water to the mixing and extruding — but the drying is really what sets apart one pasta from another. Paolo explained how centuries ago, pasta in Gragnano was dried outside. At the foot of the Lattari mountains, just a few kilometers from the Tyrrhenian Sea, the hot air rises around midday and is slowly replaced throughout the afternoon by humid sea air, which then gradually evaporates into the evening. Pasta dries here perfectly without cracking. But the Industrial Revolution brought smog and pollution, forcing pasta makers indoors. So they replicated the outside climate inside the factory. Afeltra’s elaborate drying rooms, heaters, coolers, fans and vents simulate the variable temperatures, humidity and airflow that once existed outside their doors. Slowly, over the course of 2 to 3 days, these environmental conditions create exceptional dried pasta.

Later that day, we visited another artisan pasta maker, Setaro, in the nearby town of Torre Annunziata. Vincenzo Setaro likes to do things the old way. He still sells sacks of rigatoni by the kilo to Italian nonnas at the factory entrance. He still extrudes pasta using a machine from the 1930s. And he still dries his pasta for 3 to 5 days. Some of his pastas are dried twice as long as those at Afeltra and 15 times longer than mass-market brands. Time is money, and the longer drying time helps explain why slow-dried pasta costs more.

Is slow-drying pasta just a tradition?

No. After cooking and tasting hundreds of brands, Marc and I firmly believe that pasta dried slowly tastes better. When you boil a slow-dried artisan pasta just shy of “done,” it has a nice al dente bite yet easily dissolves into a creamy paste as you chew. As the pasta dissolves, it mixes with the condiment in your mouth, creating an incredible, lush texture. The quick-dried pastas still have a nice bite, but they don’t dissolve as easily. They have a more rubbery quality and tend to bounce around in your mouth as you chew instead of melding with the sauce.

Why? It turns out that drying pasta with heat is just like applying heat to other raw foods. Vincenzo Setaro dries his pasta for 3 to 5 days at 40° to 45°C (104–113°F). That’s a relatively low temperature. Barilla, the world’s largest pasta manufacturer, speeds up the process by raising the temperature. Barilla dries its pasta for only 7 to 10 hours starting at around 55° to 65°C (131–149°F) and bringing the temperature up to a relatively high maximum of 84°C (183°F).

Have you ever scrambled eggs over too high a heat? They cook quickly and get kind of rubbery and bouncy. It’s very similar when you dry pasta at high temperatures.

The heat causes the protein molecules to come apart or “denature” and then link up with each other and form a cross-linked web of protein.

With quick-dried pasta, the high heat causes the protein web to become so extensive and so strong that it traps the wheat starch within the web. It’s like bake-drying the pasta. When you boil quick-dried pasta, the protein web is so sturdy that hot water can’t reach the starch granules as easily, so the starch doesn’t dissolve as much or “gelatinize” into that beautiful creamy paste that Marc and I love so much.

But that’s just going by feel. To try and see the difference with our own eyes, we sent samples of slow-dried Setaro and quick-dried Barilla pastas to Nathan Myhrvold, the genius behind Modernist Cuisine. Nathan and his food scientist, Larissa Zhou, cut the pastas — both dry and cooked — and analyzed them under a microscope at 20x magnification. They stained the protein and starch different colors so you can clearly see them. The pictures don’t lie. In the Barilla sample, you see the extensive protein network and the trapped starch granules within. In the Setaro sample, the protein network is less developed, leaving the starch more available to bond with water during boiling.

Barilla and Setaro are just two examples on opposite ends of the dried pasta spectrum. You’ll find every variation of time and temperature in between. And drying temperature isn’t the only determining factor. Artisan pasta makers often use freshly milled flour because it has a more pronounced flavor than flour that has been sitting around for weeks or months. They also tend to extrude the pasta dough through bronze dies, which rough up the surface of the noodles, making the pasta more porous, and that allows water to flow in and starch to flow out of the pasta more easily. Mass-market brands, on the other hand, usually extrude through Teflon, which is faster and much easier to clean than bronze. But Teflon dies create pasta with a slick surface, and sauce doesn’t stick to it as easily. Teflon-extruded pasta also doesn’t release as much starch into the water, and starchy pasta water is an incredible thickener and flavor enhancer for sauces. It’s what helps to marry pasta and sauce when you toss them together.

None of this is to say that quick-dried, Teflon-extruded pasta is somehow bad. I use Barilla pasta all the time. It tastes good. But when I want something more special, I’m willing to spend a few extra bucks for artisan pasta like Setaro. It just depends on what level of cuisine you aspire to on any given day.

That brings us back to DeCecco.

On our last night in Italy, we had dinner at La Brughiera, one of Bergamo’s best restaurants. The chef, Paolo Benigni, and owner, Stefano Arrigoni, treated us to a feast of dishes like tripe and baccala salad with red onion, eggplant Parmesan croccante with beef fillet, and fresh porcini mushrooms with foie gras. Late in the evening, Stefano sat with us and discussed the research we’d been doing for Mastering Pasta. We told him about Afeltra, Setaro, and the different pastas we’d been tasting. “A few nights ago, we had dinner at Torre Del Saracino in Vico Equense,” we explained. “The tomatoes in the spaghetti al pomodoro were amazing. They made the dish with DeCecco pasta.” Stefano rolled his eyes and said, “The chef has a deal with them. He gets paid to serve that pasta.”